The fear of authority against homosexuality in Iraq… How has it affected marginalized individuals?

Homophobia in Iraq… What are the politicians’ motives and how did it impact the LGBTQIA+ community?

“I feel like I’ve become like a wall… without any emotions, I’ve lost the desire to socialize and interact with others. I have difficulty sleeping. This incident has pushed me deep into my anxiety. It’s as if I’ve returned to my time in detention in Syria.” – Hadi, a Queer Syrian living in Erbil.

“I prefer to stay at home and avoid contact. The streets are tense wherever I go, that’s evident from people’s looks.” – Lilit, a Queer Syrian activist living in Erbil.

The following does not shed light on the stigmatization and discrimination against the LGBTQI+ community, or on the violence carried out based solely on gender identity. Rather, it focuses on some of the negative repercussions resulting from the use of the LGBTQIA+ issue as an authoritarian tool for the manipulation of public opinion to gain favor and divert attention away from themselves. This has become evident, at least in Iraq, over the past two weeks, as the echoes of this immense wave of homophobia and incitement against one of the most marginalized gender groups in the Middle East has increased.

A dangerous escalation precedent… Penalties may escalate to execution.

Homosexual relationships are considered illegal in Iraq, similar to its neighbors in the Middle East. Numerous amendments have been made to several laws since 1981, all of which condemn homosexual relationships. Although this issue has been raised in sessions of the Iraqi parliament, especially in recent years, the recent escalation is considered a dangerous precedent. The parliament announced the completion of the first reading of amendments to Prostitution Law No. 8 of 1988, which includes adding a provision criminalizing homosexuality and even those who advocate for it. Penalties may include execution or life imprisonment. The first reading of any bill in the Iraqi parliament represents the initial stage of introducing and presenting it to the members of parliament for the first time for discussion and feedback. Subsequently, a future session is scheduled to further discuss its details before voting on it in subsequent stages.

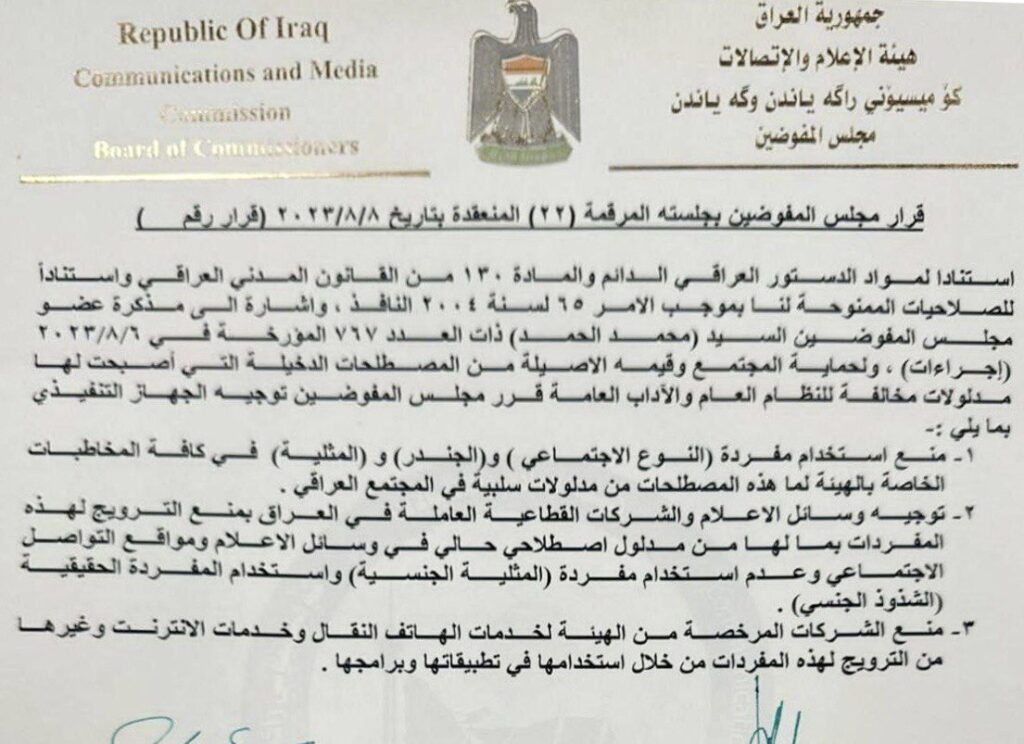

This escalation comes as another chapter in the ongoing heated debate surrounding homosexuality, sparked by the decisions of the Iraqi Communications and Media Commission to prohibit the use of LGBTQIA+ and gender-related terminology under the pretext of “protecting society.” Human rights activists have considered these successive developments as indicators of a further decline in freedom in the country, reinforcing a policy of marginalization and encouraging discrimination and ostracism not only against LGBTQIA+ individuals but also against those who sympathize with or support their cause. It appears that the repercussions have manifested themselves immediately on the streets.

Iraqi streets witnessed protests after an Iraqi refugee in Sweden, Salwan Momeka, burned a copy of the Quran. These protests were incited at the request of the religious leader Muqtada al-Sadr, and included such acts as burning rainbow flags.

Witnesses from queer Syrians in Iraq… Assault, detention, and threats.

“They beat us indiscriminately with a water hose; it left marks on my eye, back, and right ear,” narrates Hadi (27 years old), a member of the Guardians of Equality Movement specializing in providing support and assistance to LGBTQIA+ Syrian individuals inside and outside Syria. He describes the brutal assault that occurred a week ago while he and his friend were simply sitting in Sami Abdul Rahman Park in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, exchanging laughs while watching videos on their phones. This attack took place as media outlets and social media pages were responding to the government’s decisions and parliament’s threats to increase penalties against LGBTQIA+ individuals and their allies, widely condemned as acts of homophobia.

“You have no shame; why do you have earrings? Are you not Muslims?’ Suddenly, they emerged from among the trees. They attacked us with blows and insults until I had to forcibly remove my earrings because they were hitting me on them,” Hadi recalls quietly.

Hadi and his friend were then detained in a car for a quarter of an hour before being transferred to the park guard’s room. “When we were taken to the guard’s room, my friend broke down in tears. They initially threatened him by saying they would inform the police and then his father. They also threatened to revoke my residency,” he recounts.

Photos showing the aftermath of the assault on Hadi – documented by Lilit from the Guardians of Equality movement’s Point of Contact.

Lilit (32 years old) works as a point of contact with the Guardians of Equality Movement for the Iraq program, alongside a group of activists, to assist members of the LGBTQIA+ community and document violations against them. She regrets her inability to provide assistance to several cases that recently contacted her, stating, “I now feel like I’m living with less freedom by at least 70 percent. There is greater restriction on the work of activists and associations. We do not have a license.”

The repercussions extend beyond members of the LGBTQIA+ community:

Ruba Al-Hasani, a postdoctoral researcher at Lancaster University, expressed during an interview that the repercussions of banning the terms such as “gender” means “an increase in arbitrariness in state affairs management. It also violates the freedom of expression for journalists, academics, and activists.”

The Iraqi researcher also reflects the concerns of many academics in Iraq, especially those specializing in gender and women’s issues: “They cannot pursue their profession or publish their research for fear of violence, whether societal or institutional.”

Al-Hasani also points out that attempts by the parliament to legislate the death penalty or life imprisonment against LGBTQIA+ individuals or those who support them would “pose a threat to the lives of LGBTQIA+ community members and encourage violence and persecution against them.”

The repercussions of any escalation against LGBTQIA+ individuals do not stop at posing a threat to physical health alone. Many activists and human rights advocates warn of the possibility that anti-LGBTQIA+ political discourse could create a social stigma, in addition to causing LGBTQIA+ community members to feel fear, shame, and isolation. It can also lead to the denial of many of them access to employment, education, and healthcare services.

Many factors make LGBTQIA+ issues a contentious matter in the Arab world in general. However, what if the authorities intentionally provoke this controversy? Why do most Iraqi politicians align their views contrary to the trend in other Iraqi affairs? We asked the Iraqi researcher Ruba Al-Hasani about the motivations behind the decision of the Iraqi Communications and parliamentary efforts to further restrict LGBTQIA+ issues and related matters.

Al-Hasani begins her discussion by highlighting the widespread corruption within state institutions and the presence of many individuals involved in the ruling political class. This prompts the opening of this sensitive issue “to create a societal fear directed against a small segment of the population that poses no threat to others. This is one of multiple attempts to control the population by creating the ‘other’ who is feared by those who do not understand it.”

Lilit also points to the prevalence of high-level corruption and the government’s need to divert attention from it, stating, “So, the government periodically stirs this issue, for example, in a year like 2023 when we have no water in Iraq, homosexuality is the perfect subject to distract from the government’s tarnished image in the eyes of the angry population due to its failed performance.”

Slim hopes for change:

Lilit doesn’t ask anyone to accept her; she asks not to be criminalized because of her identity: “I’m not optimistic, but I hope the laws change to protect us.”

Hadi sighed deeply. Then, he expressed his frustration with the future of the rights of individuals of the LGBTQIA community and told us about his decision to suspend his emotional and sexual relationships: “I had overcome the effects of my detention in Syria and was trying to start life anew.” Hadi sighed deeply once again and said, “When we were in Syria, they taught us not to cry because it would reveal our identity, and that put us in danger.”

The Iraqi researcher Ruba Al-Hasani concludes her discussion by mentioning a feminist movement that has been active for years, advocating for legislation to protect against violence. However, she expresses her regret that the parliament “prioritizes a draft law that doesn’t protect the community and its members, but rather incites violence and hatred.”

The complexity of the legal, political, and social entanglements that bind the LGBTQIA+ community and its individuals may become increasingly complicated in the future. Therefore, the fear of homosexuality in Iraq or the Middle East is not just a social issue from a human rights perspective; rather, it is seen as a political challenge that should be addressed seriously. Conversely, for those who may view it as a limited issue, homosexuality touches on the fundamental core of human rights and individual freedoms.