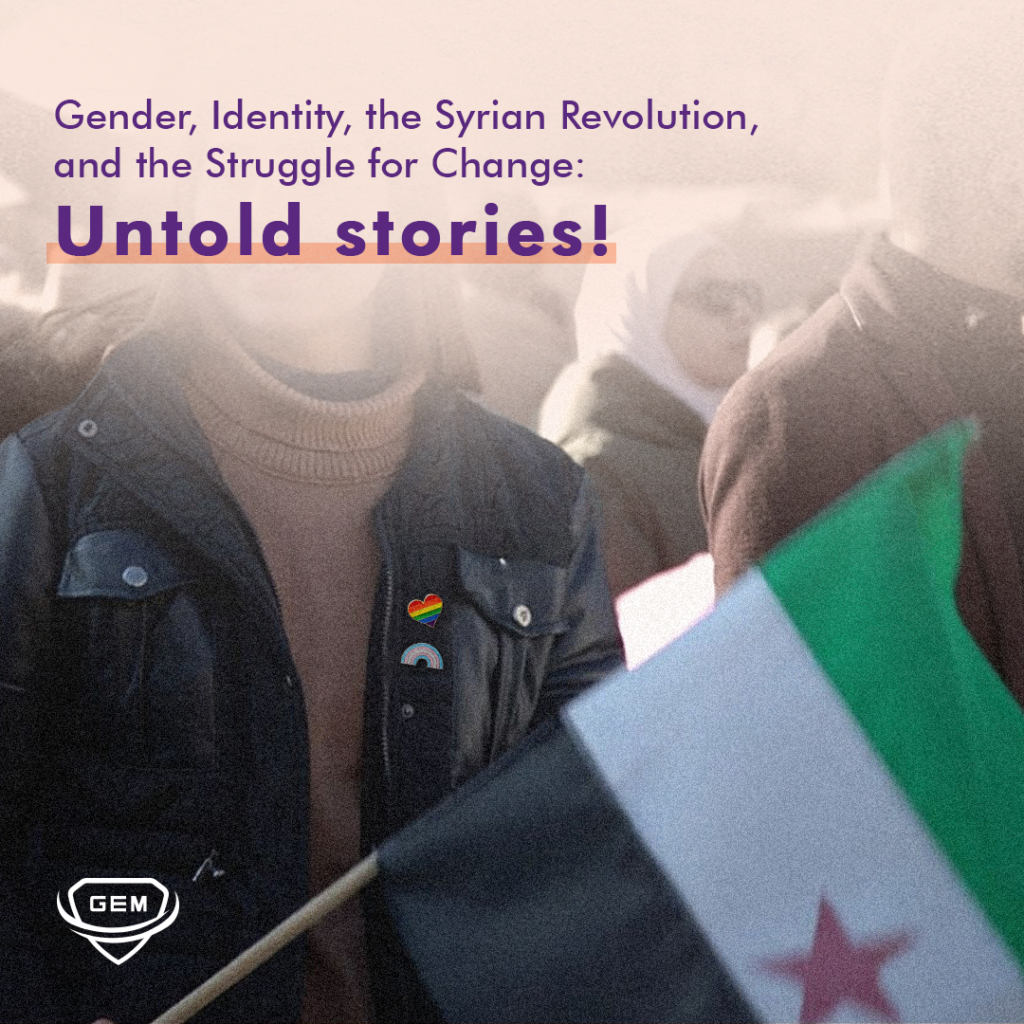

In the quest to uncover unheard voices and profound human stories that reflect the diversity of revolutionary movements against the Syrian regime in 2011—a diversity that included members of the LGBTQIA+ community in Syria—I had the opportunity, over the years of the revolution, to closely interact with many of these individuals. They did not hesitate to join the ranks of Syrians in demanding freedom, justice, and a civil state amidst a war considered one of the most brutal in modern history. This was despite the dual challenges posed by a repressive regime and a rejecting society.

The young Syrian woman, “Oula ,” did not limit herself to standing up against the political regime, leaving her job as a university lecturer, and then fighting against it with all the means at her disposal. Over the past years, she has also worked to break stereotypes, not only about working women capable of facing risks but also about the misconceptions and ready-made molds that taint perceptions of LGBTQIA+ individuals.

“Because we are oppressed, we have been with the revolution since its beginning.”

Before the 38-year-old Syrian woman became a familiar face among Syrians through her work as a journalist covering numerous events and news stories in dangerous circumstances during what was deemed the most violent war of modern times, Oula —a pseudonym she chose to use because, as a lesbian Syrian citizen, she remains “half-visible,” as she puts it—shares a glimpse into her life at the onset of the 2011 revolution. She recounts how she defied the directives of her superiors to write reports about students with opposition tendencies:

“I was a lecturer at the College of Arts at Aleppo University when the revolution began. The fear was immense. Under pressure from my department supervisor, advice from those around me, and the fear of malicious reports, I was forced to flee Syria. Since then, they have considered me defected from the regime.”

She describes the moments she participated in protests as “very terrifying,” especially the student demonstrations in front of the Faculty of Medicine over 10 years ago:

“I always made sure to be masked while protesting—not only out of fear for myself but also for the safety and security of my family.”

Oula highlights the connection between the oppression faced by LGBTQIA+ individuals and their being among the first to stand with the Syrian revolution when it erupted in 2011:

“Subconsciously, because we are oppressed, we have a stronger revolutionary inclination. We understand what injustice means. We don’t fit into pre-made molds and question everything. We’ve been with the revolution since its very beginning, and we were even among its organizers.”

Despite her departure from Syria, Oula was determined to continue her activism against the Syrian regime. She transitioned from the world of teaching and students to the world of media and journalism. Not far from the Syrian border, she initially focused her efforts in the Turkish city of Gaziantep. Over the years, she became one of the most recognized faces among Syrians.

“We exist, no matter how much we are fought. Our numbers will not decrease.”

While her gender identity did not prevent her from participating in the early days of the revolution, Oula now regrets her inability to return to Syria due to her gender identity. She believes that the same reasons that prevent her from returning to her country and becoming more involved in the rebuilding process are the very reasons hindering the LGBTQIA+ community from obtaining their rights:

“There is an unjust hatred towards the LGBTQIA+ community. We may be seen as worse than the Syrian regime in the eyes of Syrian society. This feeling is not good. I have been put in danger defending Syrians, and I still am. And the same people I defend are the ones attacking us.”

Oula emphasizes that LGBTQIA+ individuals in a country like Syria contribute to all aspects of life, though without it being publicly acknowledged. She hopes that they will be treated as citizens, just like any other person. She points out that she knows many LGBTQIA+ individuals who have made significant achievements, including those who are still in Syria:

“Doctors from the community who are still in Syria and stayed during the siege, rescue workers, journalists, as well as academics, and many others in various fields.”

In the conclusion of her conversation, she advises her community members still in Syria to be cautious, saying:

“We exist, no matter how much we are fought. Our numbers will not decrease. All that is needed is for us to keep pushing ourselves.”

This is not just a recounting of a personal interview, but an attempt to understand a small part of the many roles played by LGBTQIA+ individuals—lesbians, gays, transgender, bisexuals, intersex people, and those with non-binary gender identities—during the Syrian revolution. It seeks to explore how understanding their experiences can contribute to shaping a more inclusive and diverse future in Syria.