Introduction:

The Turkish police campaign continues to pursue, as it says, “violators” of Syrian refugees on its territory. While the principle of prohibiting forced return is one of the most essential principles of the Geneva Refugee Convention and its Protocol, to which Turkey is a party, Article 33 stipulates that “No Contracting State may expel a refugee in any way to the borders of territories where their life or freedom would be threatened on account of their race, religion, sex, membership of a particular social group, or their political opinions,” violating Article 3 of the Convention against Torture, which it signed in 1984, it was proven that the Turkish authorities were pressuring the deportees and forcing them to sign “voluntary return” papers, according to the testimonies of 11 people whose deportation from Turkey to northwestern Syria was documented by Guardians of Equality Movement (GEM). We discuss their story in this report.

The Turkish government arrests Syrian refugees and transports them to deportation centers and then to border deportation centers, and then delivers them to the border crossings after signing the “voluntary return” papers under pressure and coercion.

Each Turkish province has one or more deportation centers, also called deportation camps.

The Turkish authorities ignore the serious, life-ending risks that people may face if they are deported to Syria, especially if they are members of the LGBTQIA+ community.

Marginalized groups in Syria always face situations of physical and verbal violence based on sexual bias, such as members of the LGBTQIA+ community, and the penalty for same-sex relationships may reach death in the areas of northwestern Syria, whose residents live under the burden of escalating social, religious, political, and economic complications due to the consequences of the war and rules of life and ways of thinking that are more stringent and brought on by the control of several radical factions over the region.

The interference of sheikhs, clerics associated with factions, and non-independent legal bodies prevailed in the region of Northwestern Syria in organizing the region’s legal issues. The authorities apply in their judicial administration both the Unified Arab Law and the Syrian Arab Law based on the reference of the 1950 Constitution.

In areas under the control of the Syrian Regime, Syrian law criminalizes same-sex relations, and this charge can be based on Article 520 of the Penal Code of 1949, which states that “any sexual intercourse contrary to nature is punishable by law for up to 3 years.”

Methodology:

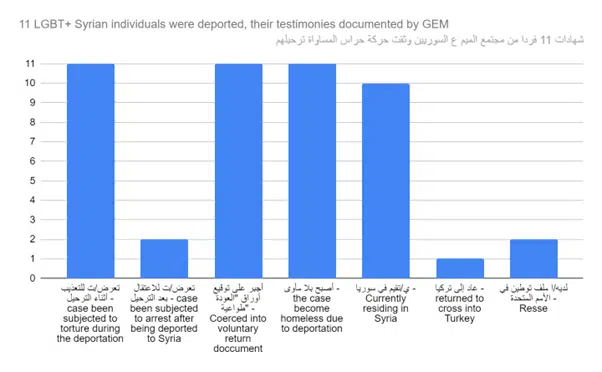

Based on the method of research, analysis, and collecting 11 testimonies from 11 Syrian individuals from the LGBTQIA+ community who were deported to Syria in the period extending from October 2023 to March 2024, we quickly shed light on the stories of 5 of them. We have coded their names at random.

Summary:

- 11 Syrian LGBTQIA+ people were targeted for deportation by the Turkish authorities despite having legal documents.

- All cases were exposed to verbal violence and abuse that Turkish immigration officers and employees carried out.

- Immigration employees and security forces put pressure on all cases to sign “voluntary return” papers.

- Two of the 11 were detained in Syria by Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (formerly al-Nusra).

- The same person who Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham arrested was detained again by The National Army that Turkey supports.

- One case out of 11 was able to cross back into Turkish territories, while the rest remained in Syria.

- All the individuals in the cases expressed their sense of danger from the continuing presence in northwestern Syria and Tal Abyad.

- Two of the 11 cases have resettlement files with the United Nations.

- All cases faced difficulties in finding shelter.

- Some cases were already suffering from a health situation that became worse after leaving, and one case is in a critical condition.

.

Background:

The regions of northwestern Syria are filled with multiple authorities, and Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham HTS (formerly the Al-Nusra Front) is considered one of the strongest groups controlling the region, as it controls the entire Idlib governorate and parts of the Aleppo countryside. The rest of the factions, known as the National Army and supported by Turkey, control the cities of Afrin and Azaz, Al-Bab, Al-Rai, and Jarabulus in the Aleppo countryside, Tal Abyad and Ras Al-Ain in the Raqqa countryside and Al-Hasakah countryside.

Despite the security chaos and lack of stability in the regions of northwestern Syria, the Turkish government continues its security campaign to pursue Syrians who it claims do not have legal papers and is deporting them to what it calls “safe areas,” which is a term used by the Turkish government to justify the procedures for deporting Syrians to areas of its influence in northwest Syria.

According to the latest government statistics, 3 million and 279 thousand Syrian refugees hold a temporary protection card, an identification card given to Syrian refugees. Several Turkish provinces, such as Istanbul and Urfa, have stopped granting it since 2019. The Turkish government requires holders of a temporary protection card to obtain a travel permit to move between Turkish provinces.

Human Rights Watch previously revealed the number of Syrians deported during the year 2023, which was approximately 57 thousand, double the number in the year 2022. The head of the Immigration Turkish Management revealed on May 5 of this year that about 111 thousand Syrians had been “voluntarily” deported to their home country since September 2023.

The deportations come amid accusations against Ankara of violating laws related to refugees and accusations of Turkish security personnel committing several serious violations, including practicing physical torture and verbal abuse against the deportees and ignoring any health condition, exceptional medical condition, or security risks to life, which is consistent with the account of the testimonies we collected in this report.

Violence, sexual harassment, and incitement:

Both (H. L.) and (M.D.) are two young gay Syrians residing in Turkey who have official papers authorizing them to remain in the country. They do not know each other, but what they have in common is that they both have resettlement files at the United Nations, but that did not prevent the Turkish authorities from deporting them to Syria.

H.L. says that police in Istanbul stopped him and asked about his papers because of his external appearance, and upon learning of his Syrian identity, they transferred him to the Tuzla camp, where he remained for two days. He was then transferred to the Harran Deportation Center, and after 4 days, he was transferred to the SANLIURFA GERİ GÖNDERME MERKEZİ BARINAN TANITIM KART camp for deportation. This camp was another turning point in a journey of horror experienced by H.L.

“When I told the camp director that I was gay and had HIV to sympathize with my condition, he cussed at and incited those in the camp against me,” says H.L, and states that this incident brought with it episodes of physical and verbal violence and even sexual harassment, “I was imprisoned in a refrigerator room inside the camp for a whole day with another group of detainees.” H.L.’s stay at the camp continued in Şanlıurfa for 15 days until he was deported to Idlib after being forced to sign “voluntary return” papers.

While M. D. was visiting Gaziantep after obtaining a travel permit under which he was legally allowed to go to his destination, he was stopped by Turkish security forces, who decided that he was in violation despite having a travel permit. “ I was beaten in front of people while I was being handcuffed and taken to the bus.”

M.D. says he was tortured by gendarmerie at the Oguzeli Pre-remover detention Center in Gaziantep, and subjected to a barrage of curses and insults when he told them that he was gay and that it was dangerous for him to be deported to northwestern Syria.

Syria.. Arrest at the crossing and transfer to a judge because of the LGBTQIA+ flag:

Immediately upon M.D.’s arrival on the Syrian side through the Bab al-Hawa crossing, security personnel affiliated with Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham HTS stopped him and interrogated him. After confiscating his phone, they found dating applications intended for members of the LGBTQIA+ community. This led to his detention, torture, and death threats, until he was transferred on the same day to undergo a forensic medical examination after denying the charges against him that he was gay.

“The results of the medical examination did not prove anything. They threatened me with constant surveillance.” M.D. was released the next day and indicated that he was forced to attend a Sharia course in the mosque.

As for H.L., there were other rounds of detention awaiting him inside Syria, which began when personnel affiliated with Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham detained him without a clear reason. He was soon released after the Guardians of Equality Movement (GEM) intervened through a protection plan, but what was more difficult was when the military police of the National Army arrested him while escaping to the city of Azaz: “After arriving in the city of Azaz, I decided to buy water, only to be surprised by members of the military police standing next to me. One of them looked at the bag on my back and accused me of trying to cross illegally into Turkey. They then searched my phone and found the gay flag logo on my phone.”

H.L. was transferred to the civil court judge in Azaz, where he would have faced a sentence ranging from five years to death according to the prevailing Arab law in the region, but the Guardians of Equality Movement and its partners were able, through the Protection Plan, to intervene to release him.

“The Police officer told me: Go to Syria and die there.”

During a visit to the Arnavutköy area in Istanbul, Turkish security forces stopped (S.H.) and asked to examine his residence documents. He says that the officers claimed that his address had disappeared from the system, and they arrested him and transferred him to a deportation camp in the Tuzla region for three days, where he was subjected to verbal and physical abuse by security personnel.

At the Tuzla Center in Istanbul, (S.H.) requested medical attention “to discuss my sexual orientation with the doctor,” but the assigned officer prevented the doctor from providing assistance “and told me: Go to Syria and die there.”

The young man was then transferred to the deportation center in the state of Keles on the border with Syria. He says that he was subjected to physical violence there for four hours until he signed the “voluntary return” papers to be sent to Azaz in the evening of the same day.

From the stage to Syria:

While the night in Istanbul was decorated with Christmas lights and the city was witnessing the beginning of new, cold winter and preparing to welcome the year 2024, (A.B.) took the stage, presenting a theatrical performance at the Arab Book Fair and while the sound of the audience’s applause still echoed in his ears on the way back to his residence in Istanbul, the Turkish police stopped (A.B.), and detained him and transferred him to the deportation center in the Tuzla region despite having a travel permit to Istanbul to perform his play.

Handcuffed, on a bus taking the road to the Bab al-Hawa crossing, which is under the control of Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham, (A.B.) arrives at the last stop before Syria in the state of Kilis. He says that after beatings and insults, he signed the “voluntary return” papers.

Pressure to sign “voluntary return” papers also includes health conditions:

Neither (N.R)’s health condition nor his possession of a temporary protection card or even obtaining a travel permit for the purpose of treatment in the state of Gaziantep prevented the Turkish Gendarmerie from detaining him, deporting him, and pressuring him to sign the “voluntary return” papers to the Tal Abyad area in the countryside of Raqqa city, which is under the control of members of the Turkish-backed National Army.

After leaving Tal Abyad Hospital and receiving treatment, N.R. is now residing with a number of Syrian young men inside collective housing that deportees from Turkey have taken as their place, but he still suffers from severe anemia, immunodeficiency, and pneumonia (or bronchitis)

Analytical summary:

The previous data shows us several points:

- The possibility of a Syrian refugee in Turkey being subjected to deportation increases if they belong to one of the marginalized social groups, such as homosexuals, bisexuals, transsexuals, or those who have a non-normative appearance or are not associated with the gender binary of male/female.

- The possibility of being exposed to physical and verbal violence by security personnel in Turkey increases when the deported person is a member of marginalized groups and communities such as the LGBTQIA+ community.

- Security personnel and immigration officials in Turkey showed discriminatory and hostile behavior toward those who identified themselves as gay or trans.

- A number of cases felt severe psychological pressure and informed police officers and the deportation camp administration of their sexual orientation to avoid deportation.

- The Turkish police campaign does not exclude those in poor health conditions or those infected with HIV.

- It appears that the campaign carried out by the Turkish authorities is arbitrary and does not target “violators,” as they say.

- The government and official media use the terms “voluntary return,” “safe zones,” and “violators” to justify widespread forced deportations.

- The term “voluntary return” is consistent with the policies of both Lebanon and Iraq in dealing with the issue of Syrian refugees.

Recommendations:

- Providing an urgent response to the deportees regarding shelter and protection.

- Providing health support and medical care.

- Providing psychological and legal support.

- Creating a mechanism to protect deported individuals who are at increased risk of deportation, such as members of the LGBTQIA+ community, and human rights defenders, such as ensuring temporary relocation or resettlement with exceptional procedures.

- Finding an international monitoring mechanism to consider potential risks and work to stop deportation and prevent any violations against deportees.

Additional questions may arise based on the previous data about the impact of the Turkish government’s security campaigns in fueling racism and tension towards Syrians and about the extent of the government’s ability to politicize refugee issues in a manner consistent with its foreign policy.